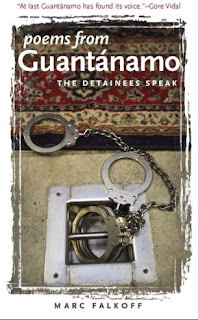

Poems From Guantanamo

I first read about the collection, The Detainees Speak, in the NY Times. I came away feeling that Chiasson maybe had glanced at a single poem in the collection as a means of attaining a couple of word bytes for his political invective against what was (obviously) thinly-veiled Bush regime propaganda funneled through (obviously) fascist, unlettered, security-clearenced translators. Obviously. I only wish I had a copy of the book in front of me so I could see how it balances out, because truly, judging from the review on Slate, O'Rourke read the whole thing and engaged the poems from a more neutral starting point. I realize that neutrality is not the perspective warranted when discussing war; but should it be different when approaching art derived from an experience of war? Poetry makes for very poor cannon fodder, either way. And that's not an insult to the art. Poetry can, in careful hands (of both poet and reader), engage a kind of empathy not attainable via CNN. Or, as O'Rourke so deftly concludes:

I first read about the collection, The Detainees Speak, in the NY Times. I came away feeling that Chiasson maybe had glanced at a single poem in the collection as a means of attaining a couple of word bytes for his political invective against what was (obviously) thinly-veiled Bush regime propaganda funneled through (obviously) fascist, unlettered, security-clearenced translators. Obviously. I only wish I had a copy of the book in front of me so I could see how it balances out, because truly, judging from the review on Slate, O'Rourke read the whole thing and engaged the poems from a more neutral starting point. I realize that neutrality is not the perspective warranted when discussing war; but should it be different when approaching art derived from an experience of war? Poetry makes for very poor cannon fodder, either way. And that's not an insult to the art. Poetry can, in careful hands (of both poet and reader), engage a kind of empathy not attainable via CNN. Or, as O'Rourke so deftly concludes:[T]hese poems both humanize their authors and keep them obscure to us. It is unlikely, then, that anyone is going to come away from reading this volume with their minds changed about Guantanamo. But Poems From Guantánamo is not about innocence or guilt, or merely an instrumental artifact in a political debate. Instead, it performs a valuable service in humanizing the individuals incarcerated there, reminding us that even those charged with crimes are people, not faceless automatons—even as it also leaves us with a potent sense of how much we don't know about them.

Chiasson was perhaps expecting clarity of political purpose in the same way any literary critic looks for precision of language. Doubtless, as both critics note, the writing itself is nothing fantastic. But, O'Rourke seems to pick up on more of the nuance - what would one expect a prisoner, possibly innocent, possibly also the victim of torture, to write? How would this person engage his subject? What kind of subject at that? And how are these inevitable questions about the REAL person behind the poem doing a service or a disservice to the poem itself?

That's where I get in a knot about "poetry of witness." Poetry has never been about current events, influencing politics, &c. At least not overtly. It's the lack of the obvious factor in so much of the poetry I read and write that leads me to steer away from defining poetry as anything like an efficient tool. It is vastly inefficient to write a poem! Why not just say the thing? Because the shifting, meandering, subverting and skirting of poem-making brings me to that which is more valuable than the thing. What that is, I can't really say, but it sure is neat.

Comments